JWT Hacking 101

December 07, 2017

As JavaScript continues its quest for world domination, JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are becoming more and more prevalent in application security. Many applications use them, so it has become very important for me to know as much as I can and I want to share what I’ve learned. In this blog post I will discuss what JWTs are and common vulnerabilities that come along with them.

What are JWTs?

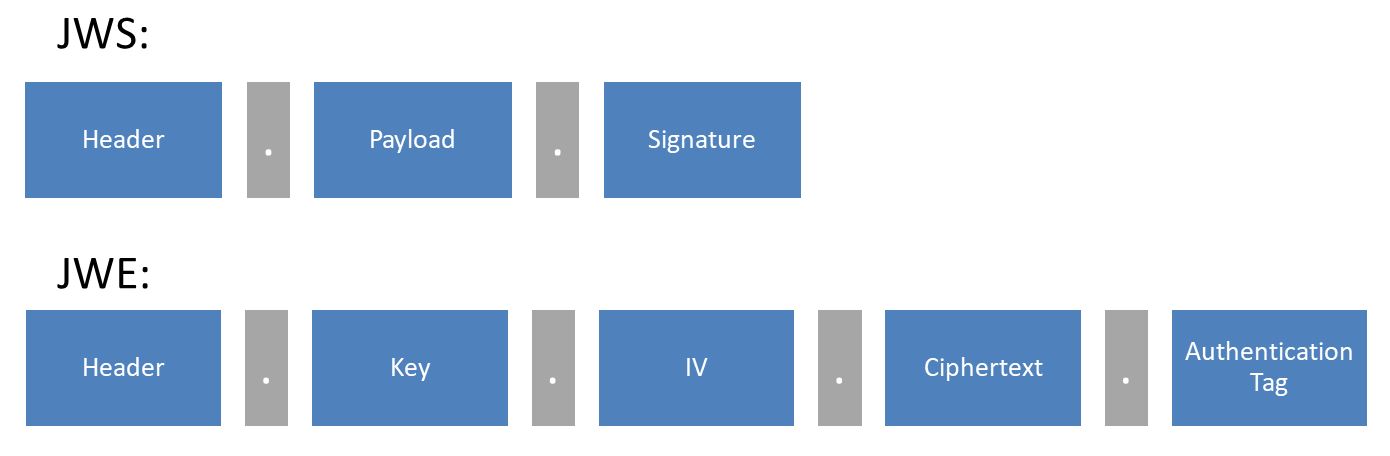

But first, I want to address a misconception. JWTs come in two varieties: JSON Web Signature (JWS) and JSON Web Encryption (JWE). JWSs are signed JSON data that are comprised of three parts, while JWEs are encrypted JSON data and made up of five parts:

Originally, I was only aware of and had only seen JWSs (not that I knew it was called that). I referred to them as JWTs. I wasn’t completely in the wrong, because all JWSs are JWTs, however, not all JWTs are JWSs. As I have yet to work with a JWE, this blog post will only cover JWTs that are JWSs. Currently, the JWT RFC only requires support for JWS to be compliant. JWE is optional functionality, as seen in the table below. Maybe that is the reason for the misconception? No matter, now back to your scheduled programming.

There is already loads of good information about the JWS version of JWTs (hence forth just called JWT) floating around, especially on jwt.io, so I’ll just cover the basics quickly. A JWT is just signed JSON data, typically for use in authentication and information exchange. The signature aims to maintain the JSON data’s integrity. JWTs are comprised of three base64 encoded parts, separated by a “.” period. The three parts are: header, payload (sometimes referred to as claims), and signature. The header typically only contains the algorithm used to sign the JSON data. The algorithms can work in variety of ways, such as a HMAC (symmetric) or RSA certificate schemas (asymmetric). The payload contains the plaintext JSON data to be signed. Finally, the signature contains the signing result of the payload and the algorithm specified in the header.

So let’s take a look at a quick JWT example signed with HS256 using “secret” as its key:

JWT:

|

1 |

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJtZXNzYWdlIjoibXkgbmFtZSBpcyB6b25rc2VjIn0.UAFZVbMwFK6nhFA_X6DHBKSJVrCNY4hzeAdUSK0rnxw |

If we decode the base64 and spilt where the “.”s are, we get the following:

Header:

|

1 2 3 |

{ "alg": "HS256" } |

Payload:

|

1 2 3 |

{ "message": "my name is zonksec" } |

Signature: (base64 encoded signature bytes)

|

1 |

UAFZVbMwFK6nhFA_X6DHBKSJVrCNY4hzeAdUSK0rnxw |

The following are the different algorithms for use with JWTs:

| “alg” Param Value | Digital Signature or MAC Algorithm | Implementation Requirements |

| HS256 | HMAC using SHA-256 | Required |

| HS384 | HMAC using SHA-384 | Optional |

| HS512 | HMAC using SHA-512 | Optional |

| RS256 | RSASSA-PKCS1-v1_5 using SHA-256 | Recommended |

| RS384 | RSASSA-PKCS1-v1_5 using SHA-384 | Optional |

| RS512 | RSASSA-PKCS1-v1_5 using SHA-512 | Optional |

| ES256 | ECDSA using P-256 and SHA-256 | Recommended |

| ES384 | ECDSA using P-384 and SHA-384 | Optional |

| ES512 | ECDSA using P-521 and SHA-512 | Optional |

| PS256 | RSASSA-PSS using SHA-256 and MGF1 with SHA-256 | Optional |

| PS384 | RSASSA-PSS using SHA-384 and MGF1 with SHA-384 | Optional |

| PS512 | RSASSA-PSS using SHA-512 and MGF1 with SHA-512 | Optional |

| none | No digital signature or MAC performed | Required |

“HS256” is the most common algorithm and is the only required algorithm that provides integrity (“none” will be discussed shortly). That’s the quick and dirty basics of JWTs.

Vulnerabilities

Here’s a list of things I look for when I come across JWTs.

Brute Force Secret

If the “HS256” algorithm is used, that means the payload is signed with an HMAC using SHA-256 with a symmetric key. Assuming we have a valid JWT, we have both a payload and a valid signature for that payload. This means we can brute force various symmetric keys and compare the signature result to the known-valid signature. If we have a match, then we have discovered the symmetric key and can modify and forge JWTs at will. There are several projects that can do this:

- https://github.com/AresS31/jwtcat (python)

- https://github.com/lmammino/jwt-cracker (node.js)

- https://github.com/brendan-rius/c-jwt-cracker (c)

- https://github.com/Sjord/jwtcrack/blob/master/jwt2john.py (converts the token to john the ripper format)

None Algorithm

As mentioned above, the JWT itself defines what algorithm was used to sign it. One such algorithm in the JWT specification is the “none” algorithm, which effectively tells a JWT implementation that there is no signature and the provided data is valid. The idea behind the “none” algorithm was for situations where the integrity of the token has already been verified. However, it was discovered that some JWT instances accepted payloads signed (not really) with the “none” algorithm in situations where the payload was not yet trusted, therefore trusting untrusted data. This vulnerability was quickly patched in JWT implementations once discovered by Tim McLean in 2015. However, poor coding or patching practices could still lead to the vulnerability.

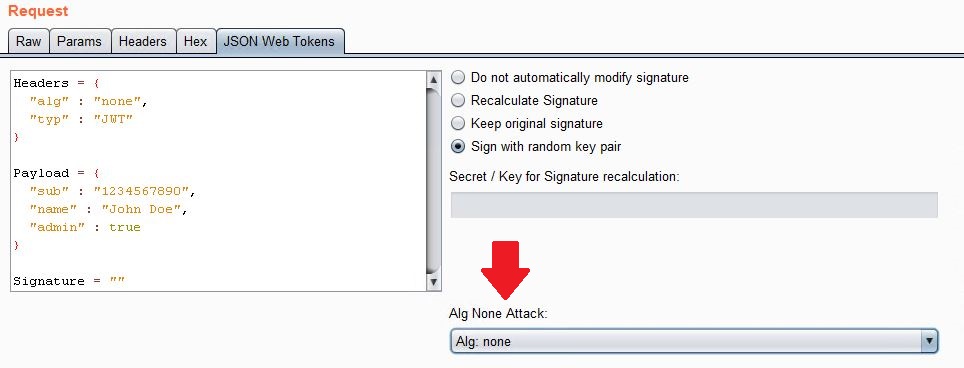

To check this during testing, we simply update the header of a JWT to be reflect “alg”: “none” and then supply an empty signature. If vulnerable, the data will be accepted and we are free to modify and forge the payload data as we please. I do this using the “json-web-tokens” extension in Burp Suite using “Repeater”, as seen in the following screenshot:

There is another great Burp Suite extension for testing this on the fly called “json-web-token-attacker“. However, it does not work with Logger++ so I do not use it often.

RSA vs HMAC

Another issue discovered by Tim McLean in 2015 was a vulnerability surrounding RSA algorithm implementation of JWTs. In an RSA algorithm implementation of JWTs, private keys are typically used by the server to sign the payload, and clients can verify the JWT using the public key. Like the client, the server will use the public key to confirm the JWTs integrity upon receiving it from a client. Here is where the vulnerability can occur. If a server’s code is expecting a token with “alg” set to RSA, but receives a token with “alg” is set to HMAC, it may inadvertently use the public key as the HMAC symmetric key when verifying the signature. This is bad because the depending on the implementation, the public key may be known to the world. Therefore, we could modify payloads, sign using public key, set “alg” to HMAC, and then be able to forge JWTs. Like the previously mentioned vulnerability, this was quickly patched in most JWT implementations, but may still exist in others due to poor coding or patching practices.

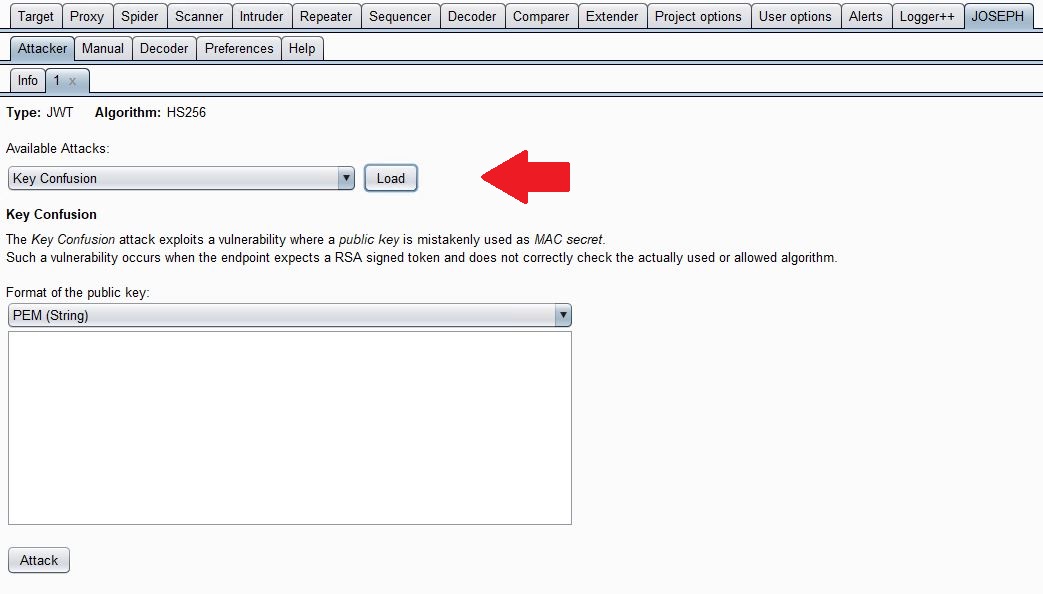

To check for this, we can use the above mentioned “json-web-token-attacker” extension for Burp Suite. It has a module for testing this as seen in the following screenshot.

Like mentioned before, it does not work with Logger++, which can make it a pain to work with. Finding the public key can be the difficult part and is totally dependent on how the JWT schema is configured. Some applications use the same RSA key pair as their TLS web server. In that scenario, we can use “openssl” to retrieve the public key:

|

1 |

openssl s_client -connect zonksec.com:443 | openssl x509 -pubkey -noout |

In other scenarios, the public key could be hard coded into a mobile application or web application, or potentially not available at all. When testing this, ask yourself who might need the public key and then try and find it.

Incorrect Implementation

This last category is sort of the catch-all. These sorts of vulnerabilities are those not against JWTs themselves, rather a flaw in how a particular application uses them.

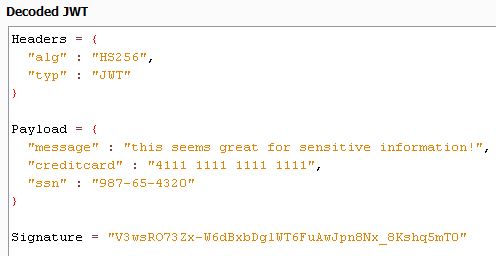

Sensitive Data in Payload

As we all know, base64 is not encryption and should be considered as plaintext. That being said, it’s entirely possible for sensitive data to be contained in a JWT’s payload and go unnoticed because of the encoding. While finding golden treasure here is unlikely (but maybe some application keeps SSN or credit card #s here?), it may be likely to find some useful information here. For example, JWTs can often be used to track a user’s permissions, back-end identification #, or other attributes. Having these extra details can come in very handy during assessments and may help uncover other puzzle pieces that you never knew were related.

As we all know, base64 is not encryption and should be considered as plaintext. That being said, it’s entirely possible for sensitive data to be contained in a JWT’s payload and go unnoticed because of the encoding. While finding golden treasure here is unlikely (but maybe some application keeps SSN or credit card #s here?), it may be likely to find some useful information here. For example, JWTs can often be used to track a user’s permissions, back-end identification #, or other attributes. Having these extra details can come in very handy during assessments and may help uncover other puzzle pieces that you never knew were related.

Open Redirects

Many Single Sign-On (SSO) solutions use JWTs to track user’s authentication status throughout the various applications using SSO. In a typical setup, a user will authenticate on the authentication server and the be redirected to whatever the end application is, along with a JWT to prove their authenticity. The end application can then verify the user’s authenticity by validating their JWT against the authentication server. SSO can be tricky, which can lead to mistakes. It’s important to understand the flow of SSO and check for weaknesses along the way. One such weakness was discovered by a coworker (@gigabuck). He found a way to manipulate where users were redirected after authentication, allowing him to redirect users and their JWT to a server he controlled, therefore stealing their JWT and session. There was a path on the authentication server, “/auth”, that redirected to the login page. The redirect parameter, “return_to”, was being validated against a whitelist of acceptable domains, however anything appended to the “/auth” resource would end up being appended to the URL the user was redirected to after authentication. To illustrate:

“/auth” would redirect to “app.server.com” after authentication.

“/auth.attacker.com” would redirect to “app.server.com.attacker.com” after authentication.

Using this, an attacker could start a phishing campaign coercing users to authenticate using their crafted link, which ultimately redirects the user’s authenticated JWT to the attacker. Additionally, if attacker had the control of an how an application server redirects unauthenticated users to “/auth” on the authentication server, the attacker could exploit this vulnerability to collect authenticated JWTs without having to get victims to click phishing links.

This vulnerability is specific to the particular SSO JWT implementation. However, it goes to show that understand the SSO flow and testing along the way can lead to interesting scenarios.

Harded Coded HMAC Keys

As we’ve seen with the brute forcing secret above, if the JWT is using a symmetric key and we can find it, it’s pretty much game over. If an application is signing JWTs on the client side, then we should be able to find the key and sign our own JWTs. The quick way to see if the JWT is being signed client side is to use a modifying proxy (BurpSuite FTW) and see when the JWT is first communicated. If it originates on the client, we can assume the JWT is being signed on the client. If it originates from the server and then the client regurgitates it, then it’s likely being signed on the server. No matter, it’s important when testing JWTs to figure how and where it is being signed. Although it may seem obvious to not sign the JWT on the client, I came across a mobile application signing JWTs on the client side using a time-based hardcoded key. In a following blog post, I will show how I reversed the mobile application and found the JWT key!

Thanks for reading and I hope you learned a thing or two about JWT. Stay tuned for the mobile application reversing blog post!